The Power of Uniqueness and Belonging to Build Innovative Teams

Humans have two basic desires: to stand out and to fit in. Companies respond by creating groups that tend to the extreme―where everyone fits in and no one stands out, or where everyone stands out and no one fits in, according to author and management expert Stefanie Johnson. How do we find that happy medium where workers can demonstrate their individuality while also feeling they belong? The answer, according to Johnson, is to “inclusify,” which is the title of her new book, Inclusify: the Power of Uniqueness and Belonging to Build Innovative Teams.

In her book, Johnson shows how companies can make a continuous, sustained effort toward helping diverse teams feel engaged, empowered, accepted and valued. Johnson, an associate professor of management at the Leeds School of Business, University of Colorado Boulder, spoke on gender equality last year at a From Day One conference in Denver. An excerpt from her new book:

I feel that when I’m here, I can be myself. I can be loud because it is too damn quiet. But when I voice my opinion, I expect the staff to push back, because I’m not always right. Then we sit down for lunch, and it feels like family dinner where we can all connect.

—Jane, manufacturing engineer

The need to belong is so innately human that no one can deny its importance. On some level we all want to be accepted by others–so much so that social exclusion causes the same areas of your brain to light up that physical pain does. Think of a time when you felt that you did not belong—when you were unwelcomed, unloved, treated with suspicion, or even ignored. How did it feel? If not painful, it was most likely not a situation you would want to find yourself in again. This is part of the reason we try to hire people who are “culture fits” with our organizations. We want to avoid having people who are unhappy or quit because they don’t fit in. But only hiring people who fit in limits the diversity of perspective needed to drive innovation. The alternative is to create an inclusive space where people—all of whom are different from one another—can fit together.

Because, just as much as we want to belong, we all want to be our authentic selves. Can you recall a time when you felt like you couldn’t be yourself? Maybe you have been in a situation where the other people in the room all held beliefs that were very different from your own and you decided to bite your lip to avoid sharing an unpopular viewpoint. Faking who we are to fit in is exhausting and we all feel most at ease when we can just be ourselves. Even more to the point, we want to know that our unique talents are valued and that our voice is heard and respected. When we feel that these two drives—uniqueness and belonging—are in balance, we feel included. The leaders who create space for their teams to experience that synergy are Inclusifyers.

Where Everyone Knows Your Name: Belonging

Everyone feels like an outsider every now and again. Think of a time when you walked into a room where there was a social gathering of the opposite sex; imagine walking in on an all-men’s cigar party or poker game if you are a woman or imagine walking in on an all-women’s baby shower or book club if you are a man (please excuse the stereotypical gender norms). Or think about how odd it might feel to be the one white person sitting at a dinner with a group of black, Asian, Middle Eastern, or Latino people. Or consider how it feels or would feel to be the only straight person at a gay bar. Women, POC, WOC, and LGBTQ people experience this all the time in the workplace. I am no stranger to that feeling. As a female professor in a top business school, I am often the only woman in the meeting room. For some time, I was the only woman in my department (and definitely the only Latina).

When I first joined Leeds I remember routinely tottering up four flights of stairs, in four-inch heels, to get to my office. Boulder, Colo., is very health conscious, and I wanted to fit in, but deep down I am a girl from LA who loves shoes and fashion. One day, I exited the stairwell and heard two of my male colleagues chatting about an upcoming happy hour. Eavesdropping on the conversation, I stepped a little closer. Awkwardly, I interjected, “Hey, are you guys doing a happy hour?” My voice cracked a little.

Silence. They stared at each other. “Oh ... uh ... we didn’t think you’d want to go. It’s a sports bar—they only serve beer.” Okay, they were right. I did not want to go. But I did want to be invited. Not being invited made me feel as though I was not part of the group. More distressing than being left out, however, was the realization that their idea of having a good time was so different from mine. It made me realize that I didn’t fit in, so even if they had invited me, I felt, I would not have been able to be myself with them.

I hear a lot of stories of people who feel as though they don’t fit in or feel excluded. I met a dapper asset manager at a conference for the National Association of Securities Professionals named Jay. He described himself as not being the typical finance guy because he was black and from the South, whereas the financial sector is dominated by white men. He explained that there is a different communication style among East Coast finance guys compared to people he was used to communicating with—mostly other black men and women in the South. When he first started in his New York firm, he was confused about why his coworkers were always laughing. Someone would make a statement about the Hamptons or a restaurant, and everyone would laugh. “What is so funny?” he would wonder. After some time he came to realize that it was just a cultural norm.

One of the toughest settings for him was big conferences where he was supposed to network. “I did not know a lot of people, and I felt like every time I tried to join a conversation everyone would stop talking and look uncomfortable.” But one year, he was invited to an after-hours get-together in some bigwig’s hotel room. “I thought I was looking good—I was wearing a black suit and tie.” When he arrived, at the room, he nervously rang the bell. He thought, “What kind of hotel room has a bell?” “The bigwig opened the door, took one look at me, and said, ‘Oh, sorry, are we being too loud?’” Jay stammered, “No, no—not at all. I, uh—I—”

“Just kidding,” said the bigwig. “I called downstairs, we won’t be needing anything tonight.” Jay’s face felt hot. The bigwig thought that he was hotel staff. “Of course, I left. I was not going to explain who I was. And the next day, I did not even go back to the conference out of fear that I would see this guy and he would realize his mistake.” Even though Jay felt as though he should belong, it was clear that to the bigwig and maybe to other conference attendees, he looked more like a staff member than a colleague.

Being mistaken for someone of lower status makes you feel as though you don’t belong in your high-status group; this phenomenon happens to women, POC, and WOC all the time. For example, one study of lawyers showed that 57% of women of color and 50% of women have been mistaken for non-lawyers including custodial staff, administrative staff, and court personnel—a phenomenon experienced by only 7% of white male lawyers. I, too, had this experience when I was asked to leave a faculty meeting because my colleague did not know I was a professor.

It was a Friday, and I was having one of those mommy mornings where I was trying to get into my smartest suit and full hair and makeup in under five minutes flat because I had kid stuff to do. But of course between milk and baby food and teeth brushing, I ruined my outfit. Outfit number two, deodorant marks. Drat. Number three: a black dress, blazer, and boots. Perfection. I was trying to look my professional best for a faculty meeting, which feels silly in retrospect but felt overwhelmingly important at the time.

I dashed into the building a little later than I would have liked because of all the outfit switching and darted up the stairs. I waltzed into the conference room, made eye contact with a couple of people, said hello, and started to sit. Before my tush hit the seat, the person running the meeting stammered, “St-Stefanie, you can’t be in this meeting. You have to go.” I felt my face flush. Was the meeting only for tenured faculty? (I was an assistant— meaning pretenured—professor at the time.) I looked around and saw other pretenured faculty. I tried to figure out what was going on but thought I should probably get out of there as fast as I could. I felt like a child who had just gotten in trouble. Even if I could have convinced him that I belonged there, it would have been too embarrassing to bear. Now, to be sure, if this were to happen today, I would ask for clarification as to why I should not be there. But that day, in my young self-conscious state, I simply scampered out of the room.

When I got to my office, my heart was beating in my throat. I closed my door and tried to catch my breath. A couple of minutes later, I heard bap, bap, bap on my door. I yelped, “Yes,” and got up to open the door. There was my colleague. Still stammering, he apologized and explained that he had mistaken me for an instructor and it was a meeting for tenure-track faculty. There is a social hierarchy in academia. Research, or “tenure-track,” faculty are the high-status bunch, and teaching faculty are lower status in terms of both pay and workload because they teach more and don’t produce research. In my department, there were few women on the research faculty, but the majority of teaching faculty were women.

The colleague said he had realized his mistake as soon as I had left the room. I imagine that someone else had pointed it out. The worst part was experiencing the feeling that Jay, the dapper asset manager, was trying to avoid by skipping the conference the next day. I had to face the person who had just excluded me—not to mention all of my colleagues, who winced and made the awkward “sorry about that” face.

It was an easy mistake to make. When there are few female professors but lots of female teaching faculty, if you meet a woman, she is more likely to be teaching faculty than a professor. It is a probability issue. But the message that I heard, as much as I tried to deafen myself to it, was that I was perceived as low status by those around me. And that is the message that women, POC, WOC, and LGBTQ often hear when they are mistaken for the help, for secretaries, or for spouses of “real” employees.

These types of interactions are often meaningless to the person doing the excluding, but across research studies, subtle and often unintentional jabs like mistaking someone as being in a lower-status position or calling them by another person of color’s name (often called microaggressions) have the same effects as, if not worse effects than, blatant discrimination on outcomes such as job performance, turnover, and mental health.

On the flip side, feeling as though you belong creates an entirely different perspective. How do you feel when you really belong to a group that you care about? What is the result of that feeling? The thing about leaders is that they have the power to ensure that people are not left out—the power to create space for everyone to be welcomed and be a part of the team even if they are different. That’s how leaders create belonging, by welcoming people to fit in while supporting them in their desire to stand out.

Shine Bright Like a Diamond: Uniqueness

At the same time as we want to belong, we all have the desire to be unique. Individualism is essential to the American spirit. We want to know that our unique talents are valued and that our voice is heard and respected. We want to be ourselves and have others welcome us because of who we are. Would it be possible to make myself look more professorial? Maybe wear elbow patches? Or dye my hair gray? Could Jay, the financial analyst from the South, learn to speak Yuppie and laugh at jokes about the local country club? Of course, but if you have been a certain way your whole life, why would you want to change it? It is part of who you are, and changing it seems to imply that your way is somehow less. If I tried to look more professorial I would feel less authentic and less confident. I want to be accepted as myself. And my research shows that most people feel the same.

The struggle over how to be ourselves and still fit in has affected teens and young adults for generations, though the desire to be one’s true self is especially strong among millennials and Gen Zers who have been told their entire lives to “be yourself” and “do you.” I remember an Asian-American girl I grew up with in Alhambra, Calif., named Tran. She changed her name to Alice—many Asian Americans in my community changed their names to sound more Caucasian. But Alice is a common name, so over the years she changed it to Allis, Allyce (pronounced al-eese), and Allie. She wanted to be unique just as much as she wanted to fit in. We all willingly give up tiny bits of ourselves—at least on a temporary basis—every day. But then there are elements of ourselves that we resist abandoning, even for a moment. Those are the characteristics that make up our identity—the way we want to see ourselves and want to be seen by others. For example, if someone asks you, “Who are you?” or says, “Tell me about yourself,” the attributes that immediately come to mind likely reflect your identity.

The struggle over how to be ourselves and still fit in has affected teens and young adults for generations, though the desire to be one’s true self is especially strong among millennials and Gen Zers who have been told their entire lives to “be yourself” and “do you.” I remember an Asian-American girl I grew up with in Alhambra, Calif., named Tran. She changed her name to Alice—many Asian Americans in my community changed their names to sound more Caucasian. But Alice is a common name, so over the years she changed it to Allis, Allyce (pronounced al-eese), and Allie. She wanted to be unique just as much as she wanted to fit in. We all willingly give up tiny bits of ourselves—at least on a temporary basis—every day. But then there are elements of ourselves that we resist abandoning, even for a moment. Those are the characteristics that make up our identity—the way we want to see ourselves and want to be seen by others. For example, if someone asks you, “Who are you?” or says, “Tell me about yourself,” the attributes that immediately come to mind likely reflect your identity.

For me, the first two aspects of my identity that come to mind are professor and parent. If someone asks me to tell them about myself, I think of these aspects of my identity, depending on the context or situation. I am a business professor who studies the intersection of leadership and diversity. Or ... I am mom to Katy and Kyle, the world’s smartest, funniest, most perfect children.

But if you were to dig deeper, other aspects of my identity would emerge. First, I am a Mexican American female. Even though people generally perceive me to be white (which I am, half white) my Hispanic heritage is central to who I am. I am a woman—and I love being a woman. I was raised Catholic and am deeply committed to family. Because these identifiers are such a deeply ingrained and important part of me, I don’t want to hide them—even in the workplace. In addition to our personal identities, we have social identities that describe our membership in groups that are salient to us. For example, I might identify with my church group, my work group, my book club, or my university (Go, Buffs!). Of course, everyone has both individual and social identities.

For some people, their race is very central to their identity, whereas for others, it may not be as important but their gender or sexual orientation might be particularly important. Further- more, in one of the greatest advances in gender and identity theory over the last 50 years, Kimberlé Crenshaw developed the idea of intersectionality, pointing out that you cannot understand one identity (such as being black) without understanding other identities (such as being a woman) so that being a black woman is something different from just the combination of being black and being a woman. Indeed, such intersections greatly affect how we are viewed by others and how we view ourselves. Individuals with intersectional identities are constantly trying to navigate the complexities of fitting in or standing out in multiple competing ways.

Regardless of which aspects or intersections of one’s identity are salient, it is difficult for anyone to feel accepted when he or she is forced to hide a central aspect of who he or she is. I’ve seen the strain that this type of masking can cause in minorities who feel that they have to “act white” and in women who feel that they have to “act like men” to succeed at work. The tension of not feeling like part of the group or not being able to be yourself can create emotional exhaustion and cause you to leave your job.

Although masking is a fairly common practice, no other masking has hit me quite so hard as that of friends in the LGBTQ community who have told me that they had to pretend to be straight or cisgender. My friend Brianna Titone, the first transgender state representative in Colorado, told me how difficult it had been to live an unauthentic life, pretending to be someone society expected her to be. Her friends, family, and community had helped to give her the strength to come out as a woman. It might have helped that she lived in liberal Colorado and surrounded herself with open-minded individuals.

I remember reading about football star Ryan O’Callaghan. He was an offensive tackle for the New England Patriots and the Kansas City Chiefs, and he was gay—a fact he hid from the world, including his closest friends and family, for almost three decades. At six-foot-seven and 330 lbs., he could certainly pass as a stereotypical straight guy. But he also knew that playing football was a great cover for his homosexuality. So when a shoulder injury threatened to take away his “beard,” he turned to prescription pills to numb the pain and eventually hit such a low point that he decided to end his life. All the pretending was finally too much for him.

But the story has a happy end thanks to an Inclusifyer. The Chiefs’ general manager, Scott Pioli, had repeatedly sent the message to his players that not only were they a cohesive team— they had to be to thrive on the field—but they were also human beings, loved and respected for who they were as individuals. That, combined with the encouragement of a therapist who suggested he might want to see how people reacted to his news before attempting suicide, might be why O’Callaghan, in an incredibly brave move, came out to Pioli in his office just after the season ended in 2011.

Pioli, a huge advocate for LGBTQ rights and gender equality, was unfazed by O’Callaghan’s revelation. In truth, Pioli had been in similar situations with other athletes. He was happy that O’Callaghan trusted him enough to share such personal information with him. “I want to know about people—their real selves,” Pioli told me. “Maybe people see that I seem like a safe space to them. So players are willing to share this stuff with me, and I want to be there for them.” This small act of Inclusifying was so important that it literally saved O’Callaghan’s life by giving him the acceptance he needed to be who he really is.

That is what Inclusifyers do. They don’t pretend that they don’t see race, gender, or sexual orientation, as many people proudly proclaim. To reinforce uniqueness, pretending race and gender don’t matter just does not work; it does not promote the integration of diversity to create greater learning organizations. I heard this message loud and clear when I visited the late CEO of the health-care giant Kaiser Permanente, Bernard Tyson, in his Oakland office. I asked him what was different about his approach to diversity, and he explained that his approach is to notice and celebrate difference. “We don’t pretend, we don’t walk around talking about how we’re color blind. We don’t do that. We face the difficult issues and conversations.”

Pretending that we don’t see race or gender is actually hurtful to people of color, women of color, and women. First, if you don’t see race, for example, what do you see when you meet an Asian person? To me, if you don’t see their race it means “I don’t view you as less than; I see you as white.” But can you see how that is insulting? It suggests that white is the norm and the ideal. Second, seeing everyone as being the same actually denies people their basic human need of uniqueness. I think of my race and gender as something that adds value to the conversation, rather than something that should be ignored. Third, ignoring gender or race denies the fact that someone might have experienced sexism or racism in the past. And to negate those experiences sends the signal that you don’t care about that person.

Uniqueness + Belonging = Inclusion

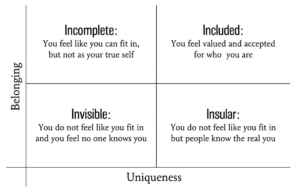

Without both of these essential ingredients, one cannot feel included. At the worst end, you can imagine feeling that you don’t belong and your uniqueness is not seen. This causes employees to feel invisible. What does that look like in the workplace? Invisible employees are often shift workers or remote workers, who may actually go unseen by their coworkers. But you may also feel invisible if your job role is discounted by those around you. For example, cleaning staff often go unnoticed in the office. No one makes eye contact with them, no one says hello, and no one acknowledges their work. Being totally ignored can cause you to feel dehumanized, to experience shame, and to want to quit your job. But feeling invisible is not limited to support staff. Research studies show that women, POC, and WOC often feel invisible at work, receiving a lack of eye contact from their peers, feeling excluded from social events and work discussions, and being talked over, ignored, or discounted during meetings. In fact, many faculty of color report being mistaken for the cleaning staff. The result of making people feel invisible is lowered well-being, mental health, productivity, and commitment to the job.

You can also imagine feeling that you are accepted, but only when you “cover,” or “code switch,” to fit in. This causes people to feel incomplete because they have a sense that they belong, but only insofar as they are willing to deny their unique identity. In an effort to fit in, individuals might change their appearance, alter their language, and overlook bias from others. But all that faking can limit the extent to which teams benefit from your unique perspective, can cause you to experience reduced authenticity, and can isolate you from other members of your identity group.

We most often think of women, POC, WOC, and LGBTQ individuals hiding aspects of themselves—but really this is a phenomenon that plagues many people with stigmatized identities, or things about ourselves that we hide to avoid being judged or excluded. For example, people might hide the fact that they grew up poor, deny religious beliefs, or obscure a disability. But covering is problematic because sharing information about yourself yields a suite of benefits from mental health to interpersonal connections with others.

On the other hand, some individuals who are recognized for their uniqueness still do not feel included because they are faced with harassment, discrimination, or social isolation as a result of their identity. In this case, you feel insular—detached and alone. Hearing people in the halls planning a casual lunch and not being invited, hearing conversations go on around you in meetings while you are not invited in, or having your work accomplishments overlooked in comparison to others shows you that some people belong, but you do not. Individuals can also feel a lack of belonging when they feel tokenized for their identity or pigeonholed as the “diversity person” when that is not the role they have chosen. And it is not only women, POC, WOC, and LGBTQ people who experience this feeling—solo men or whites can also feel insular in cases where they are the ones left out as a result of their race and gender. Engagement and performance suffers, and you might quit to avoid the feeling of isolation you’re experiencing.

Contrast these feelings with when you feel included: valued and accepted for who you are. You feel that your ideas and contributions are recognized and that you are an essential member of the team. You feel engaged, you work hard, and you want to go to work. This is the goal of leadership: to create inclusion so that employees’ work is beneficial to their organization and those employees benefit from working in that organization. Rather than ignoring difference, Inclusifyers create a team where everyone belongs because they know that acknowledging everyone’s unique talents and perspectives strengthens the organization. It is really about finding ways to help everyone contribute to the team’s goals and feel like a valuable piece of the group.

In my research, I have found that most leaders want to achieve these outcomes. They want their group members to feel engaged, supported, and included. They just don’t always know exactly how to get there, or they make tiny missteps that impede their success. Usually, these mistakes are the result of myths that obscure their view of the world around us and hold them back.

INCLUSIFY Copyright © 2020 by Stefanie K. Johnson.

Reprinted here with permission of Harper Business, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers

The From Day One Newsletter is a monthly roundup of articles, features, and editorials on innovative ways for companies to forge stronger relationships with their employees, customers, and communities.