HR, How Did You Get So Influential? The Evolution of a Profession

Long before the notion that you could love your work, the HR profession was founded on the fact that work could be harmful to your health. In many ways, the profession's growing focus on well-being is not a touchy-feely detour, but a natural outgrowth from its roots–maybe even a nod to its origins.

“The birth of human resources today came out of the concerns for individuals, starting off with their actual physical concerns,” says Barbara Holland, HR knowledge advisor at the Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). “It’s moved well beyond that at this point.”

Born on the dangerous shop floors of the Industrial Revolution, human resources has been gathering responsibilities, but not losing any, for 100 years. Where it once was charged with the physical safety of workers, HR’s list of responsibilities now includes employees’ mental, financial, and social well-being, and it’s contending with AI and all its practical, ethical, and regulatory implications.

The HR department of 2023 takes on more workload and influence than ever before, and many practitioners are shifting to strategic roles and automating tasks that were once the purview of the “personnel department” of 50 years ago, like benefits enrollment, tax documentation, and fielding FAQs. They’re freeing up time to focus on the more creative elements of the job, like developing leaders, creating equitable work environments, and bolstering employee well-being.

How did HR get here, and where is it going? From Day One spoke with HR scholars and specialists to provide perspective about how the last three years of disruption fit into the longer game.

In the 20th century, HR went through a tremendous amount of existential change–it evolved from protector of safety to negotiator to compliance officer to paper pusher to strategic business partner–and as of the 21st century, it has come full circle. In many instances, HR has again assumed its role of employee advocate. Now, the profession is tapping into policymaking, giving employees a seat at the table and a say in their working conditions.

The Modern Origins of HR: The Safety and Well-being of the Worker

The modern practice of human resources originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in response to the dangerous working conditions of the Industrial Revolution. “As there were factories and more workers working in one place, that’s really where the whole idea of a personnel department started,” said Kristie Loescher, who teaches HR and management at the McCombs School of Business at the University of Texas at Austin.

Not only were the physical working conditions dangerous, “the emotional and psychological hazards of working consistently in these conditions were immense as well. Long hours, limited sustenance, and impersonal treatment contributed to an already stressful work environment,” wrote the academics Robert Lloyd and Wayne Aho in their paper, “The History of Human Resources in the United States: A Primer on Modern Practice.”

Miserable conditions led to the proliferations of labor unions and their calls for workplace reforms. For instance, following the infamous Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire in 1911, in which 146 workers were killed as a result of locked doors and inadequate escape routes, both the city and the state of New York passed dozens of workplace safety laws in response to pressure from newly formed unions, community organizers, and the general public.

Labor unions gave workers a say in their working conditions, and the National Labor Relations Act of 1935 compelled employers to give them a seat at the table. Now that there was a need for someone to negotiate with the unions, the discipline of “industrial relations” was born.

HR Becomes a Compliance Officer

By mid-century, among HR’s chief concerns was compliance with regulation. Following the passage of laws that protect employees from discrimination in the workplace–including the Equal Pay Act of 1963, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which established the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and the Age Discrimination in Employment Act in 1967–installed a department designed to keep the company from getting sued. Its stance was a defensive one, said Holland.

Under the new name “personnel,” what would become the modern HR department was steeped in the bureaucracy of mitigating legal risk and all the record-keeping it requires. Exchanges between HR and the workforce were minimal and transactional.

Andrea Osborne, who has more than three decades of experience in HR and is currently the VP of people for the product team at the software company Genesys, describes the mentality of the HR department of that time like this: “Here’s your badge, here’s your documentation, here’s your tax paperwork. Bye! I’ll see you on your way out the door.”

HR Becomes a Business Partner

The globalization of business spurred the changes that produced the influential HR department of today. Companies turned their attention to the strategic capabilities of the HR department when, in the 1970s and 1980s, it became increasingly clear the U.S. was now competing in a global economy.

In a paper on the international perspective of HR, Randall Schuler and Susan Jackson, both scholars of HR, wrote that “during that period, the focus of business shifted from domestic to multinational to global; the speed at which business was conducted increased; organizations recognized that labor costs and productivity must be address from a world-wide perspective; and many companies realized that competitive advantage could be seized and sustained through the wise utilization of human resources.”

SHRM’s Holland began her HR career in the mid 1980s, driven to improve the cool and distant personnel department she encountered in the past. Holland saw transformation beginning to take place. “We were looking to make a difference,” she said. “I came in right on the cusp of the old still hanging on with some organizations, but newer organizations really embracing that HR was more than just a police department and signing people up with their paperwork and then walking around making sure nobody was breaking the rules.”

HR operations itself benefited from globalization, according to Holland. “You had influences from other cultures and how people management was handled based on wherever their headquarters was.”

At the same time, the U.S. transformed from a manufacturing economy to a “knowledge” economy. Where we once made products, we now made services, and that required a new approach to employer-employee relations. “If I have analysis work to do, and customer service work to do, and work that requires more autonomy on the part of the worker, all of a sudden I have to treat that worker very differently. As jobs changed, the way we treated employees had to change,” said UT-Austin’s Loescher. “This whole new area of HR was added in the ’80s and ’90s about employee engagement and development–that if we invest in our employees and give them working environments that are satisfying and then help them develop and learn and grow, they’ll not only be ready for today’s challenges in our business, but they’ll be ready for tomorrow's challenges.”

James Bailey, who teaches leadership development at the George Washington University School of Business, noted the influence of social science research in the 20th century, which asserts that people, not factories and machinery and financial assets, determine future business success. “It’s culture, it’s selection, it’s finding the right people, it’s properly motivating them to do their work better,” Bailey said. “Why you can have two firms of equivalent assets and one far outperforms the other is because of the people factor.”

Though labor unions declined in popularity by the 1980s, Thomas Kochan and Robert McKersie noted in their 1989 paper “Future Directions for American Labor and Human Resources Policy,” the “rising expectations of workers for increased influence over their immediate work environment and long-term careers.” Following a period of bureaucracy that kept distance between employer and employee, the HR department now had to operate with employer and employee best interests in mind.

As companies had to compete in a global economy that could access to talent all over the world, business strategies were adapted to include skills development and employee engagement. According to Loescher, “the profession was changing from one of mere rule implementation and screening of applicants to one where it included connection to the business strategy as well as a connection to the analysis and design of jobs that not only would meet the strategic need of the company, but would be motivating for people to do,” said Loescher.

The “personnel” department became “human resources,” and in university classrooms, moved from industrial relations to business schools, said Bailey. HR was officially a business asset.

Human Resources Becomes the People Department

HR practitioners today will have noticed another change to the department’s name. Just as the change from “personnel” to “human resources” marked a change in the existential purpose of the department, the more recent shift to “people operations” reflects the further expansion of the function in business.

“Currently, even the term ‘human resources’ does not seem to convey the importance of human capital as we’ve moved more into a ‘knowledge’ economy, in which human thought, creativity, and innovation are critical to the success of new economy businesses,” said Sherry Moss, the associate dean of MBA programs at the Wake Forest University School of Business.

In corporate America, the new term is “people operations,” in academia, it’s all about “human capital management,” marking “yet another step symbolic of ‘We are part of the capital that makes this organization function and we want a seat at the table,’” said GWU’s Bailey.

Automation of repetitive tasks, or ones that are at least more easily handled by software and AI, frees practitioners to focus on the strategy of developing talent and better workplaces. As mundane functions are automated, “it will leave more opportunities for the HR business partners to have more human interactions,” said Amy Freshman, senior director of global HR at the HR software company ADP. “Automation will certainly help remove the repeatable mundane tasks. At the same time, what is being asked of HR is changing. In many ways it’s growing, which just adds more to the plate.”

As the department gets more involved with the human elements of business, its reputation among employees is changing dramatically. Kam Hutchinson, a global director of talent acquisition who has spent more than a decade working in HR, said workers are more open to interacting with HR than they were in the past. “There’s more of an openness to reaching out to HR for support and seeing them as an advocate for you and not necessarily for the company,” she said.

The HR Department of the Future is Proactive

So, what comes next? As HR cements itself as a key player in business success, where is there to go?

HR is no longer just a responsive organization. Its latest goal is anticipation, prediction. For instance, contributing to the excitement around the new discipline of “people analytics” is its potential for predicting things like employee engagement or employee attrition.

And the leaders in the department aren’t just thinking about what goes on inside a company, they’re considering the outside influences as well. When Jackson and Schuler wrote their article in 2005, they noted HR’s growing responsibility to monitor the external environment. As people operations is called upon to respond to national crises, social unrest, and mental health needs, that responsibility is even greater today.

Holland believes the next HR frontier is public policy. In the last handful of years, SHRM has become involved in influencing lawmakers. Its Government Affairs team has advocated in Washington for policies like paid leave, removing barriers to employment for immigrants, and employer-sponsored education assistance.

“Where before we were a reactionary industry or occupation to what’s happening in employment law and things like that, now we’re inserting ourselves to try to actually influence that before the law is made,” said Holland. “HR is trying to actually influence change before it hits us.”

Emily McCrary-Ruiz-Esparza is a freelance reporter and From Day One contributing editor who writes about the future of work, HR, recruiting, DEI, and women's experiences in the workplace. Her work has appeared in The Washington Post, Fast Company, Quartz at Work, Digiday’s Worklife, and Food Technology, among others.

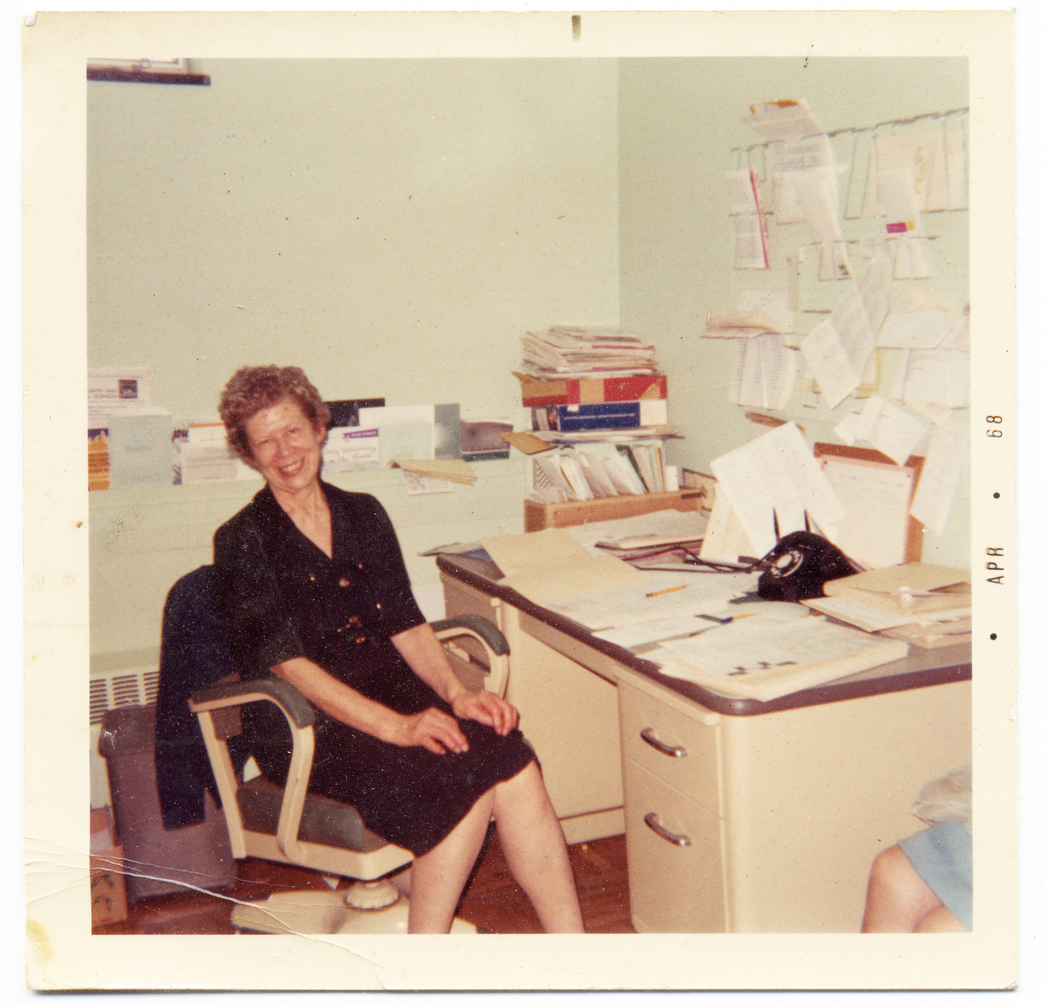

(Featured photo by Violeta Stoimenova/iStock by Getty Images)

The From Day One Newsletter is a monthly roundup of articles, features, and editorials on innovative ways for companies to forge stronger relationships with their employees, customers, and communities.