How One CEO Broke Capitalism—and How We Can Fix It

In his role as the Corner Office columnist for the New York Times from 2018 to 2022, David Gelles interviewed hundreds of CEOs. In those interviews, one name consistently came up: Jack Welch, who served as chairman and CEO of General Electric between 1981 and 2001.

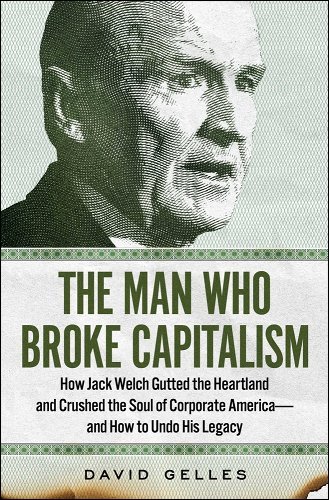

“They would bring up his name unprompted, sometimes as an example of everything they thought was wrong with the economy, and that alone was telling because it suggested he was a reference point for people trying to create a different kind of economy,” Gelles said in a fireside chat at From Day One’s May conference in Brooklyn, where he spoke with fellow Times reporter Emma Goldberg about his new book, The Man Who Broke Capitalism: How Jack Welch Gutted the Heartland and Crushed the Soul of Corporate America–and How to Undo His Legacy.

If that title sounds epic, so has been the rise and fall of Welch’s standing as a corporate role model. Back in 1999, Fortune magazine named him “Manager of the Century,” explaining, “Welch wins the title because in addition to his transformation of GE, he has made himself far and away the most influential manager of his generation.”

In his book, Gelles explains how this came to pass. Welch produced uncanny financial results, which held Wall Street in thrall. “When Welch took over, GE was worth $14 billion. Two decades later, the company was wroth $600 billion–the most valuable company in the world,” Gelles writes. “All that material success obscured darker truths. Welch was not, as he would have liked us to believe, a patrician steward of sound business judgment and good character. ... Rather, he was hungry for power and thirsty for money, an ideological revolutionary who focused on maximizing profits at the expense of all else.”

Before Welch came along, that wasn’t the prevailing ethos, either at GE or Corporate America in general. While capitalism before Welch was hardly equitable, it was a very different ballgame than the one played today in terms of winners and losers. “If you look at a GE annual report from 1953, they proudly talked about how much money they were paying their workers. It was a good thing. The more money they paid their workers, the better,” Gelles said in the fireside chat. “They talked about how they were investing in their communities, and trying to make the cities where they operated their factories better, more wholesome places. And they even talked about how much money they were paying the government. They were proud to pay their taxes.”

Welch introduced different tactics that would completely reshape GE and the rest of the American economy, a process Gelles called “relentless, ruthless, deliberate.” Welch embraced three core components: massive downsizing, outsourcing and offshoring, and stack ranking of employees, which utilizes bell curves to rate and rank employees based on performance and is used to cull low performers from the workforce.

These tactics are still practiced by corporations today, Gelles pointed out. WeWork relied on stack ranking even as it was raising billions of dollars; Amazon’s Jeff Bezos has sought for “transactional” relationships with warehouse employees; and companies like Chipotle are regularly sued for labor violations. Gelles, who reported extensively on the root causes of the fatal crashes of two Boeing 737 Max jetliners, said they were the result of a corporate culture that prioritized profits over safety.

After the downfall of GE, which was tied heavily to the financial crisis of 2007-08, Welch went on to spread conspiracy theories about President Obama and support President Donald Trump. “Into his retirement, he started essentially being an internet troll,” Gelles said. A seminal moment was both Welch and Trump got behind a 2012 job reports conspiracy.

Even though Welch kicked off a decades-long, strategic dismantling of worker’s rights and well-being, Gelles believes that capitalism can still be saved. “Creating an alternative that’s viable and still allows companies to thrive and prosper and be profitable–because I’m a capitalist too–is going to take a long time. We are, though, at this moment where something seems to be shifting in the ethos of business,” he told the crowd.

The last chapter of his book outlines what could come next: a commitment and actual action from business leaders to take care of workers, communities and the environment, as well as legislation designed for a more equitable economy. Gelles takes hope in a culture shift that’s beginning to acknowledge that Welch’s idea of capitalism isn’t sustainable: “It’s been a shift in tone and messaging that is long overdue, of course, but we didn’t even see ten years ago.”

Emily Nonko is a freelance journalist based in Brooklyn, NY. In addition to writing for From Day One, her work has been published in Next City, the Wall Street Journal, the Guardian and other publications.

The From Day One Newsletter is a monthly roundup of articles, features, and editorials on innovative ways for companies to forge stronger relationships with their employees, customers, and communities.